The Clubhouse

Community leader, friend of the Japanese community, and realtor, Hung Wo Ching, arranged the purchase of three lots at 520 Kamoku Street. The lots totaled 21,600 square feet and cost $1.05 per square foot.

The Building Committee, headed by James Lovell, accepted the bid of $58,350 by contractor D.K. Nagata to build the clubhouse. A large piece of marble was imported from Carrara, Italy for a memorial plaque that was installed in the clubhouse. The names of all 100th soldiers who were killed in action were inscribed on it.

Later, another committee headed by Robert Sakoki studied the feasibility of adding an apartment building on vacant land adjacent to the clubhouse. Financing was secured, and since its completion, rentals from the apartments have provided a source of revenue for the Club’s operations.

In 1952, ten years after the idea of a postwar organization and clubhouse was proposed during a time of great uncertainty, the building was completed.

Honoring their Comrades

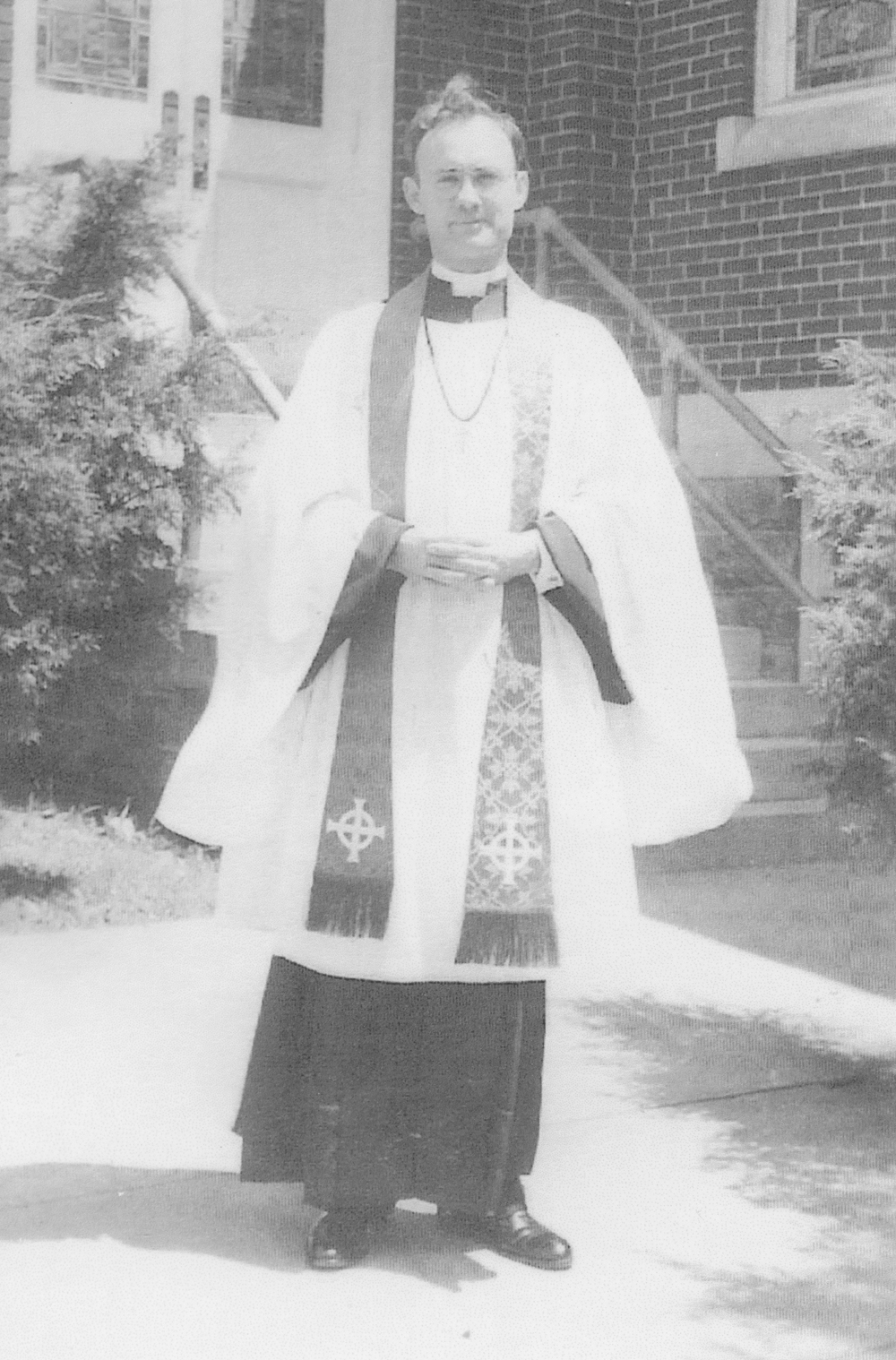

In 1947, the annual memorial services on the different islands were conducted by the battalion’s Chaplain Israel Yost who travelled from Pennsylvania to Hawaii. These services were scheduled on the last Sunday of September, the Sunday nearest the death of the first Nisei soldier killed in action, Shigeo “Joe” Takata.

In 1947, the annual memorial services on the different islands were conducted by the battalion’s Chaplain Israel Yost who travelled from Pennsylvania to Hawaii. These services were scheduled on the last Sunday of September, the Sunday nearest the death of the first Nisei soldier killed in action, Shigeo “Joe” Takata.

The following September, the remains of 79 soldiers from Hawaii who had died in combat were returned from overseas cemeteries. Representatives from the 100th, 442nd, and Military Intelligence Service clubs were on board a Coast Guard cutter to greet the incoming ship. Veterans attended services for their comrades in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (Punchbowl) and country cemeteries in the Islands. Taro Suzuki, an original officer of the 100 th Infantry Battalion, served as the first superintendent of this new national cemetery.

A History of the 100th

Farrant Turner and James Lovell commissioned Dr. Thomas Murphy, a history professor at the University of Hawaii, to write a book about the battalion. Lovell, who was the chair of the history committee, provided documents and arranged interviews with the veterans. The book also included information about the social, economic, and political conditions before, during, and after the war that affected the Japanese community, especially in Hawaii. The book, “Ambassadors In Arms: The Story of Hawaii’s 100th Battalion,” was published in 1954 and remains an important source of information about the battalion.

Puka Puka Parade Newsletter

The first issue, April 1946, was published with veteran Samuel Sakamoto editing this initial newsletter. A contest to come up with a name of the newsletter was announced, with the winner receiving a prize of $10.00.

While some veterans furthered their education using the G.I. bill, others started small business. In the early days of the PPP, veterans placed ads announcing their services – auto repair, service stations, taxi service, grading, trucking, masonry, carpentry, plumbing, electrical, cabinet making, termite control, landscaping, florists, watch repair, clothing manufacturer, photography, cafes and grocery stores, real estate and insurance sales.

Issues of the Puka Puka Parade can be found at: https://evols.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle/10524/11835

As of 2020, it is still being published by the sons and daughters of the veterans.