America’s First Japanese American Chaplain Served America’s First All-Volunteer Japanese American Military Unit

At the outset of World War II, the Reverend Masao Yamada was four years into his ministry at the Hanapepe Japanese Christian Church on the west side of the island of Kauai. He was 35 years old, not very tall, slightly rotund, nearsighted and a bit absentminded. But he was absolutely fearless.

In the days after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Yamada took it upon himself to meet with U.S. military officials on Kauai. He wanted them to know that Hawaii’s Americans of Japanese ancestry (AJA) were loyal to America and he asked for their help. When the officers told him in a hostile tone that they had no interest in helping Japanese American women and children, Yamada replied, “If you hate us so much, why don’t you just shoot me?” The officers were taken aback and didn’t know how to respond to him. The next day, Yamada received an official apology from them.

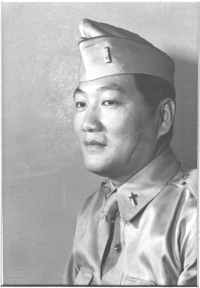

Two years later, Reverend Masao Yamada became the first American of Japanese ancestry to be commissioned a chaplain in the United States Army.

The son of a plantation carpenter, Yamada was born on April 10, 1907, in the West Kauai village of Kaumakani, a sugar plantation community that was also known as Makaweli. At the tender age of 12, Yamada’s parents sent him to Oahu to board at the Okumura Boys’ and Girls’ Home, where he would have access to a better education. In the process, he was converted to Christianity by the Reverend Takie Okumura, who had emigrated from Japan in 1894.

Yamada graduated from McKinley High School, which had a large population of Japanese American students, and then went on to the University of Hawaii (UH).

Yamada learned organizing and leadership skills from Okumura and put them to good use as a youth leader at the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) while attending the university. After graduating from UH, he applied for a job in the YMCA program, only to learn that it had been given to a younger and less-experienced white undergraduate at a much higher salary. Yamada protested by immediately going to see Frank Atherton, the president of the Honolulu YMCA. He told Atherton he was quitting his job because of the blatant discrimination that had been dealt him. Atherton, who also happened to be a major financier of Hawaii sugar plantations, was so impressed by Yamada’s forthrightness that he arranged for him to attend the Auburn Theological Seminary in upstate New York. Yamada continued his training at the Andover-Newton Theological Seminary in Boston, Massachusetts.

He returned to Hawaii in 1933 and was ordained a Christian minister. He was then sent to Kona to minister to Japanese immigrants at the Central Kona Union Church.

In 1935, he married Ai Mukaida. Convinced that he needed to be able to speak Japanese fluently in order to truly preach the gospel, he and Ai moved to Japan to undergo language training. Within a year, however, Japan’s military government labeled him a “pacifist” and asked him to leave the country.

By 1937, Yamada had returned to his native Kauai and began ministering at the Hanapepe Japanese Christian Church. The war broke out while he was serving at Hanapepe. Yamada was asked to lead the Kauai chapter of the Emergency Service Committee, an organization of young Nisei who helped develop the local AJA population’s response to the crisis.

When the 442nd Regimental Combat Team was formed in 1943, the unit learned that Caucasian chaplains had been assigned to them. Reverend Yamada convinced Hawaii military officials that they needed to broaden their thinking and volunteered to serve as the unit’s chaplain. Yamada’s son, Armin, recalled his father’s reasoning: “My father knew from experience that the [AJA] boys from Hawaii were going to suffer prejudice when they went to the Mainland, and if he didn’t go, there wouldn’t be anyone to speak up for them.”

At age 37, Yamada was commissioned a captain in the U.S. Army. On May 31, 1943, he left his wife Ai and their three young sons — John, Armin and Gaius —on Kauai to enroll in the U.S. Army Chaplains School at Harvard University.

By late August, he had completed Chaplains School and headed south to join the 442nd, which was in basic training at Camp Shelby in Mississippi. Yamada was assigned to 3rd Battalion. Acutely aware of the strain that the government-ordered internment of Japanese Americans had placed on many families, including sons who had left their families behind in camp to volunteer for the 442nd, Chaplain Yamada decided to visit the Jerome Relocation Center in Arkansas. He was deeply affected by the sadness and depression of the people. Yamada decided to use the visit as an opportunity to deliver a sermon about “the Christian anger” he felt about the prejudice and discrimination being imposed on AJAs.

Not surprisingly, Yamada’s pointed sermons made some of the Caucasian chaplains at Camp Shelby uncomfortable and, for a time, neither he nor his fellow 442nd chaplain from Hawaii, Hiro Higuchi, were assigned specific tasks like the other chaplains. One of the white chaplains assigned to the 442nd would later tell him that America was for Anglo-Saxon Protestants and that it would be best if all of the AJAs returned to Japan. Yamada’s response was typical: He prayed that the chaplain would have a change of heart, but he also urged his commanding officers to request that a Japanese American chaplain from the Mainland be recruited so that the young AJA soldiers from the Mainland would have someone with whom they could identify. The Reverend George Aki from Fresno, California, who himself had been interned, was ultimately selected.

Despite the challenges, Yamada remained undeterred. In letters to his wife Ai, he wrote about how difficult it was to be a supervisor in a military organization of young, often-bored AJA men who fought each other in their quarters and sometimes provoked brawls with Caucasian units in restaurants. “I don’t see any glory in such action,” he wrote, ruefully.

But Yamada would also write home about the pride he felt when he saw the fit and well-trained young men of the 442nd on parade. And, he wrote about the sadness he felt in knowing that these young men, despite have been born on American soil, were prepared to die to prove their loyalty to America.