A Natural Leader of Men

“It was in the chill of one early evening at the hillside village of San Michele that the Major returned to the front after recovering from wounds. Morale was low when the men came down from the barren, snow-covered hills of Radicosa and Venafro, but the return of the Major had an electrifying boost to the morale of the men for they had suffered the cold, snow and the loss of several of their comrades. The Major didn’t have to speak; his return to the battalion now dwindled by casualties was enough to bring hope and new spirit among the haggard assortment of very tired men.”

—Puka Puka Parade (February 1952)

Such respect and admiration—as described in this passage—is the stuff of movies. In this case, however, the character is real. The Major is James Lovell, executive officer and, briefly, commander of the 100th Infantry Battalion.

Lovell was born on Feb. 6, 1907, in Hastings, Nebraska—seemingly a world away from the Hawaiian Islands and the lives of the Japanese American youth he would later come to lead. In Lovell’s mind, however, his old hometown was not so different than his new one. “The people of Nebraska are pretty down-to-earth people,” Lovell observed, “and we had quite a few Oriental people in Nebraska… it was not a difficult transition to Hawaii at all.”

Lovell was in his third year at the Nebraska Teacher’s College in Kearney, Neb., when he was recruited to teach in Hawaii. “I had offers to teach at other places, but most of them appeared to my parents as ‘not going anyplace,’” Lovell explained. “I had another year of school left, and my father wasn’t in approval of the places where I had offers of jobs—until the offer to come to Hawaii. His remark was, ‘Now you’re going someplace.’”

Lovell, then 23, graduated from the University of Nebraska in 1930 and took a position at Washington Intermediate School in Honolulu, where he taught mechanical drawing and coached a variety of sports, including football, basketball and track.

After three years, Lovell transferred to Roosevelt High School, where he taught and coached for six years before moving to McKinley High School. He continued teaching and coaching at McKinley under its influential principal, Miles Cary, and was named Dean of Boys his second year. Lovell’s tenure at McKinley, however, was abruptly interrupted by the outbreak of World War II.

Teaching and coaching brought Lovell close to his students, and those who would later serve in the 100th were pleased to learn that Lovell would be one of their officers.

Lovell had begun his military career in his home state of Nebraska, where he was a member of the National Guard. He joined the Hawaii National Guard in 1931, shortly after arriving. In 1942, he was handpicked by Lieutenant Colonel Farrant Turner, commander of the newly formed Hawaiian Provisional Infantry Battalion—later renamed the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate)—to serve as executive officer and second-in-command of the battalion.

For a time, Lovell also fulfilled the duties normally handled by the S3 (planning and training officer). After arriving at Camp McCoy, Wisconsin, the 100th’s unique situation became clear to Army brass. “There was no table of organization for a ‘bastard outfit’ such as us. We had no parents, no regiment to turn to,” Lovell reflected. “In a military set-up, there was no such thing as a ‘separate’ battalion. So… I had to work up a table of organization.”

Shortly after the unit landed on the Mainland, Lovell was ordered to report to Washington, D.C. He took the table of organization he had devised with him. The plan called for the 100th to set up its own supply section so they could acquire uniforms, equipment, food and transportation. It had five rifle companies, an anti-tank platoon, a dentist and two doctors—all features not normally allowed for a battalion.

“We formed our own outfit based on this plan that I had written,” Lovell said. “The plan was approved and was handed to us when we landed in Italy. Later, that plan was used throughout the whole military.”

More than his organizational skills, it was Lovell’s battlefield demeanor, leadership and sheer guts that made him legendary amongst the soldiers of the 100th Battalion. Leighton “Goro” Sumida says, “The Major was a real gutsy guy. But the thing I remember, too, is that he always stood up for ‘da boys. On the Mainland, if the guys get into trouble with the haoles and they get locked up in jail li’dat [like that], he would go down get his boys out. He stayed with ‘da Hawaii boys and backed them up 100 percent!”

“On one occasion, I remember when our company, E Company, was moved up to take over A Company’s place because they got shot up. We had one of the boys in the cornfield, wounded on the leg… (Lovell) got good scolding from the Colonel because he went off the road and into the bushes to go get the person in the cornfield. He picked him up and carried him back. The Colonel said, “You’ve got no business going out there! Next time let the medics get him!’ But that was the Major—all the men respected him.”

In another encounter near Alife, Italy, Sumida described how Lovell inspired his men simply by example. Sumida, serving as a scout, and a (BAR) rifleman came to a bridge. “That’s when we first heard that ‘Screaming Meemie’ rocket,” Sumida recalls. A soldier under the bridge got hit and killed, but the men on the bridge miraculously escaped unscathed. “We was all hugging the ground under the rocket barrage, but the Major, he behind the corner eating fruits and smoking his pipe. He look at us guys, and said, ‘What’s the matter boys?’ We were kinda embarrassed.”

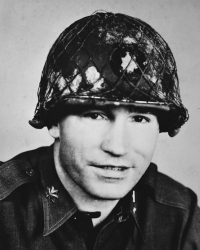

!['Coach' Major Lovell [Courtesy of Sandy Tomai Erlandson] 'Coach' Major Lovell [Courtesy of Sandy Tomai Erlandson]](https://www.100thbattalion.org/wp-content/gallery/veterans-officers/cache/tomai_sam_019.jpg-nggid03493-ngg0dyn-200x0x100-00f0w010c011r110f110r010t010.jpg)